ChessBase 17 - Mega package - Edition 2024

It is the program of choice for anyone who loves the game and wants to know more about it. Start your personal success story with ChessBase and enjoy the game even more.

December 2021 There’s only one topic to write about this month, isn’t there? The world championship match. I am, of course, referring to the Petrosian-Spassky match of 1969. Come on, readers, you didn’t think I was going to write about Carlsen vs Unmemorable, did you? I should explain that ‘Unmemorable’ is how Facebook auto-translates ‘Nepomniachtchi’ (Непомнящий – learn to pronounce it!) from Russian into English. They’ll have to fix that if the brilliant Russian claims Magnus’s crown.

I’ve no doubt that our Executive Editor will have a lot to say about the current clash of the titans, so to avoid duplication it’s safer for me to yield to my overpowering urge to look back and relive a few moments from the first world championship match which I followed in some detail.

I wasn’t a competition player when Petrosian defended his title against Spassky for the first time in 1966, so the 1969 world title match between the same players was new and exciting to me. Title matches were a veritable marathon in those days – 24 games, played at the then standard classical rate of 40 moves in two and a half hours, with adjournments after five hours. I followed progress via Leonard Barden’s next-day reports in The Guardian.

Often the game would be adjourned so that you would be kept in suspense for a further day, rather like a two-part TV mystery drama, but this could be fun as it meant you had a day to debate the adjourned position with fellow chess addicts. Sometimes there would be a disappointment: you would open the newspaper expecting to find a new game to enjoy, only to read that it had been postponed for a couple of days due to a player’s indisposition. The rule allowing players to take a time out was originally intended to cover genuine illness, but by this time it was routinely used to take a day or two off, often for tactical reasons.

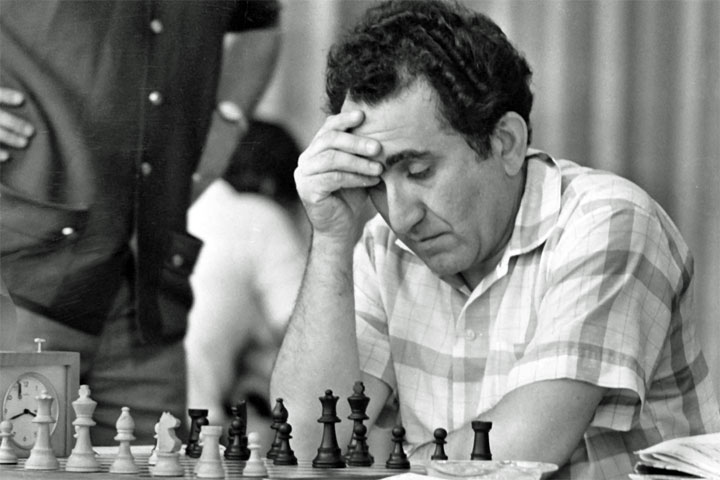

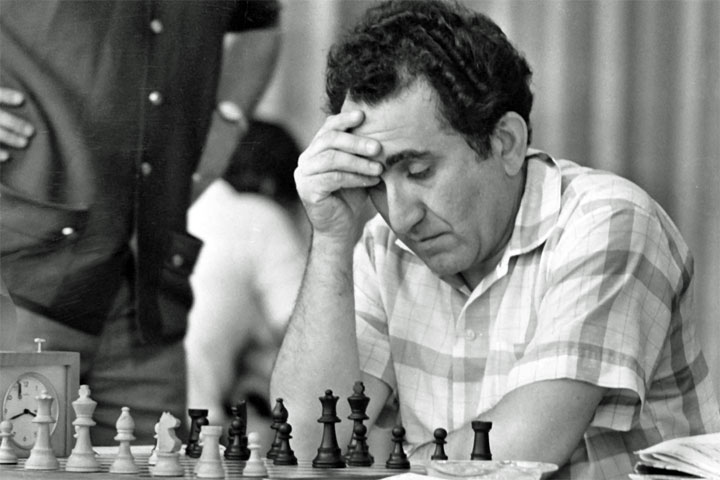

Tigran Petrosian famously defeated Boris Spassky on the black side of the Torre Attack in their 1966 match, but three years later it was all about his defending the Petroff – or not.

One question sticks in my mind about the 1969 match. Why did Petrosian stop playing the Petroff? A bit of background first: Petrosian won the first game of the match, but Spassky then hit back with three wins in Games 4, 5 and 8. However, Petrosian rallied to win Games 10 and 11. At the halfway mark the match score was level. Bear in mind that Petrosian only needed to draw the match to retain his title.

For Game 13 Spassky switched back from 1 d4/1 c4 to 1 e4, which he had played in Games 1 and 3, but with scant success. The game continued 1...e5 2 Nf3 Nf6, the Petroff Defence. Iron Tigran playing the Petroff sounds like the very definition of a tough defence, and indeed it was as he navigated to a comfortable 25-move draw. Spassky tried 1 e4 again in Game 15: Petrosian played the Petroff again and obtained an even easier draw in 19 moves.

They were still all-square when they sat down to play Game 17. It followed a two-day postponement requested by Spassky, suggesting he needed some time to come up with a way of breaking down Petrosian’s defence. Once again it was 1 e4. At this point Petrosian surprised the world by not playing 1...e5. Instead he played 1...c5 and eventually lost. Game 19 was another Sicilian and this time Petrosian lost calamitously. He managed to win Game 20, but he never got back on terms with Spassky who duly won the match.

I still don’t understand why Petrosian switched away from the Petroff when Spassky had yet to find a viable answer to it. Compare and contrast Kasparov-Kramnik in 2000, when the challenger’s stubborn espousal of the Berlin Defence was the decisive factor in wresting the title (though it’s true he switched to a different line of the Ruy Lopez in one game).

Looking back at the 1969 match reveals a few other surprises. When Petrosian defended with the Petroff in Game 13, he became the very first player to do so in a world title match. Given the Petroff’s long history and solid reputation, that might raise a few eyebrows now, but Petrosian’s adoption of the Petroff was described as a “sensation of the first magnitude” by Peter Clarke in BCM, with BH Wood making a similar comment in our own magazine.

I ran a search on the use of Petroff’s Defence in world championship matches and tournaments, and found there have been just 21 of them. The next Petroff after Petrosian’s initial pair in 1969 was when Korchnoi lost to Karpov with it in Game 4 of their 1981 match. Karpov and Kasparov both defended Petroffs against each other in their 1984, 1985 and 1990 matches, with the only decisive result being Karpov’s loss in the 48th game of the 1985 match. That’s two wins for White, with Kramnik being the only player to win from the black side when he beat Leko in Game 1 of their 2004 match. The remaining 18 draws underline the modern perception that the Petroff is a highly reliable drawing weapon for Black at the highest level. Most recently Caruana used it twice to thwart Carlsen in 2018.

I should also add that Petrosian’s Petroff in Game 13 was the first time he had played it himself in any game of which a record exists. He went on to play it a further seven times in his career, including in his 1971 Candidates match with Fischer, plus against some other top-level GMs. He drew all nine of his Petroff games.

Peter Clarke tried to make sense of Petrosian’s abandonment of the Petroff in Game 17, but his argument was unconvincing. BH Wood commented: “Quite a puzzle, this. Why, at level scores, after the all-too-easy draws of the 13th and 15th games, does Petrosian suddenly abandon the Petroff?” But then he adds: “And in the Sicilian, why does he play the line that had him at a disadvantage in the first game instead of the Dragon that brought him an easy draw in the third? The answer is that he is now playing for a win with Black!” Equally unconvincing: the jury is still out.

Had Petrosian persisted with the Petroff, it might well have been him and not Spassky who defended the title against Fischer in 1972 and chess history would have been very different.

You can go to our Live Database and search for "Petrosian Spassky 1969", to retrieve all the games of the match and play through them with engine evaluation.

You can go to our Live Database and search for "Petrosian Spassky 1969", to retrieve all the games of the match and play through them with engine evaluation.

The above article was reproduced from Chess Magazine December 2021, with kind permission.

CHESS Magazine was established in 1935 by B.H. Wood who ran it for over fifty years. It is published each month by the London Chess Centre and is edited by IM Richard Palliser and Matt Read. The Executive Editor is Malcolm Pein, who organises the London Chess Classic.

CHESS is mailed to subscribers in over 50 countries. You can subscribe from Europe and Asia at a specially discounted rate for first timers, or subscribe from North America.